What Is VC-able in Africa’s Renewable Energy Space Today?

Introduction

Africa’s energy transition is a story of both extreme need and emerging innovation. While the continent faces an annual energy investment gap in the hundreds of billions, far beyond what public and DFI budgets can meet, venture capital remains disproportionately low in the space. Since 2019, climate-tech startups in Africa have collectively raised $3.4 billion, yet this dwarfs the $277 billion per year needed to hit the continent’s climate and energy access targets.

Much of Africa’s renewable funding today flows through DFIs, infra funds, and blended vehicles. Not VCs. As a matter of fact, since 2016, when I stepped into the renewable energy projects world, very few times did it occur to me to approach VCs for funding. That’s because most investment opportunities are capital-intensive and long-dated: think grid-scale solar, hydropower, or the more popular solar hybrid minigrids. These metrics don’t meet the traditional VC playbook of fast growth, asset-light, digital, high-return exits.

Yet within this broader space, some segments are inherently VC‑able - meaning they align with venture capital’s natural appetite for scalability, technology leverage, margin expansion, and exit potential. In this article, I map the full energy landscape, relying primarily on my experience on the continent so far & incorporating data-backed facts, distinguishing what’s not VC‑able from where the real VC opportunity lies, and thus offering a practical playbook for VCs who want to enter Africa’s clean energy space, today, without misallocating capital.

I unpack the sector through a lens tuned to:

VC’s risk/return profile: scalability, margins, digital leverage, and exit pathways,

Empirical evidence: case studies, performance metrics, and investor appetite, and

Insights from the full breadth of my experience developing and delivering renewable energy projects across several African markets. My perspective is shaped by nearly a decade of working at the intersection of engineering, finance, and impact in Nigeria, Sudan, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Mozambique, the United Kingdom, etc. This dual vantage point, hands-on project delivery in frontier markets and investor-facing structuring, informs the way I analyse what is, and isn’t, truly VC-able in Africa’s renewable energy space.

I. VC Criteria vs. Infrastructure Capital

When investors hear “renewable energy in Africa,” they often conflate two very different types of opportunities: infrastructure plays and venture plays. Understanding this distinction is critical because it explains why so much money in African energy today comes from DFIs and infrastructure funds, while VC capital lags far behind.

The Venture Capital Lens

Venture capital is designed to back businesses with the potential for exponential growth, not steady incremental returns. VCs typically evaluate opportunities against five major criteria:

Scalability

Can the business grow rapidly across multiple markets or customer bases without proportional increases in cost?

Example: A service company that can expand from 100k to 1mn households using mobile money platforms, without having to triple its operational staff or infrastructure.

2. High Margins & Unit Economics

Gross margins matter. VCs want evidence that, as volumes increase, margins either hold or improve through economies of scale

Example: SaaS-based analytics company that can be replicated across dozens of markets and/or geographies with near-zero incremental cost.

3. Speed & Time-to-Scale

VCs usually expect companies to demonstrate meaningful traction within 3–5 years. Projects that take 7–10 years just to become cashflow positive don’t fit the VC model.

4. Exit Pathways

Ultimately, VCs must return capital to their LPs. That means exits via IPO, strategic M&A, or secondary sales, often in USD.

5. Asset-Light & Technology-Enabled Models

The more a business depends on software, platforms, or consumer-tech layers, the more VC-friendly it is. Hardware-heavy, capital-intensive projects tie up cash and slow scale.

Put: VC thrives where the business resembles technology, not infrastructure.

The Infrastructure Capital Lens

Infrastructure investors, on the other hand, look almost in the opposite direction. They value predictability and stability over hypergrowth:

Stable, Predictable Cashflows

A 20-year Purchase Agreement, denominated in USD, is gold for infra funds. They don’t mind 8–10% returns if they’re stable and inflation-linked.

2. Capex-Intensive Assets

Infra funds specialize in raising debt and equity for large, capital-heavy projects.

They expect high upfront spend, low operating costs, and stable yield.

3. Risk Mitigation Tools

DFIs and infra funds actively deploy political risk insurance, partial risk guarantees, and concessional tranches. Not tech. The goal is not speed, but risk-adjusted certainty.

4. Long Horizons

Infra funds operate on 15–20-year horizons. They’re comfortable locking capital for a decade or more, provided cash flows are secure.

5. Lower Expected IRRs

Typical infra returns: 6–12% IRR, often debt-heavy and low multiple. Perfect for pension funds and sovereign wealth capital, but far below VC expectations.

Why This Distinction Matters for Africa

This distinction explains why Africa has so far attracted tens of billions in concessional and infra capital, but relatively little venture capital. The problem isn’t lack of opportunity — it’s misalignment.

II. What’s Typically Not VC-able

Not every renewable energy investment in Africa is fit for VC. In fact, most megawatts installed fall firmly into the infrastructure category, capital-intensive, long-term projects that deliver steady but modest returns. Admittedly, projects in these segments are crucial for Africa’s development, and as you might imagine, have been the focus of roughly 60–70% of my experience in the sector so far. Let’s break down the most common non-VC segments.

A. Grid-Scale / Utility-Tied Renewables

Grid-connected hydro, solar, and wind farms are the backbone of Africa’s clean energy transition, similar to markets in other continents, but they do not align with venture capital’s growth expectations.

1. Market Landscape

Africa’s utility-scale hydro, solar, and wind pipeline exceeded 10 GW by 2023, with most capacity concentrated in South Africa, Egypt, and Morocco (IRENA 2023 Africa Energy Outlook).

These projects are almost always structured around Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with utilities, often state-owned, locking in tariffs for 15–25 years.

2. Typical Financials

Capex: $750k–$1.2mn per MW installed.

IRR: 6–12%, depending on tariff, location, and risk mitigation.

Tenor: 15–20 years, debt-heavy financing structures.

3. Case Studies

Benban Solar Park (Egypt):

Capacity: 1.65 GW.

Financing: $4bn, led by IFC, EBRD, and other DFIs.

Investors: Scatec Solar, ACWA Power, Norfund.

IRR: Estimated 8–10%.

Why not VC-able: Long-term infra economics, requires huge upfront debt, low multiples.

Ngonye Solar (Zambia):

Capacity: 34 MW.

Investors: Enel Green Power, IFC.

Tariff: $0.06/kWh, among Africa’s lowest at the time.

Why not VC-able: Exemplifies the “race to the bottom” on tariffs that infra funds can tolerate but VCs cannot.

Lake Turkana Wind Farm (Kenya):

Capacity: 310 MW, Africa’s largest wind project.

$680mn financing package (Norfund, Finnfund, AfDB).

Took over 10 years from conception to commissioning due to legal and transmission delays.

Why not VC-able: Illustrates how long-dated risk, legal battles, and reliance on transmission infra kill VC suitability. In the 10 years it took between conception to commissioning, a VC, ideally, would have consecutively invested and exited two investments.

4. From My POV

Over the course of my career so far, I have had the opportunity to be involved in the feasibility and scoping of 3 grid-scale (>4 MW) solar projects: one in Egypt, another in Morocco, and the last one in Nigeria. You want to know how many of them are operating today? None. Yes, none. These projects were plagued by extremely long development cycles during which the market landscape changed, legal battles for planning, approvals, insurance, guarantees, etc., power purchase agreement negotiations & battles that seemed to drag on forever.

5. Verdict

Grid-scale projects are essential for decarbonising national grids, but their risk/return profile is tailor-made for infra funds and DFIs, not venture capital.

B. Minigrids (50 kW — 1 MW)

Minigrids have been touted as the silver bullet for Africa’s 600M people without electricity access. While transformative socially, they remain a poor fit for VC economics.

1. Market Landscape

Over 3,000 minigrids currently operate across Africa, with another ~9,000 in the pipeline, World Bank 2022 Mini Grids State of the Market.

Countries leading deployment: Nigeria, Tanzania, Kenya.

Project sizes: typically, 50 kW to 1 MW; often solar-hybrid with diesel backup.

2. Typical Financials

Capex: $2,000–3,000 per connection.

IRR: 8–15% (with subsidies), but highly variable.

Tariffs: Often $0.40–0.80/kWh to recover costs — high compared to urban grid tariffs.

3. Case Studies

CrossBoundary Energy Access (CBEA):

Fund has raised >$150mn for minigrids across Africa.

Uses blended finance (equity, concessional debt, grants).

Returns in the 8–12% range, viable for infra investors but not VC multiples.

PowerGen Renewable Energy (Kenya, Tanzania, Nigeria):

Developed >100 minigrids, backed by Shell New Energies, DOB Equity.

Struggled with profitability at scale — heavy reliance on grants and DFI backing.

Nayo Tropical Technology (Nigeria):

Installed 500 kW minigrids with World Bank support.

Challenges include tariff affordability and reliance on subsidies.

WeLight (Mali, Madagascar, Uganda):

Joint venture backed by Axian, Sagemcom, and Norfund.

Installed dozens of village minigrids.

Struggles with revenue collection and security challenges in fragile states, How we made it in Africa & The New Yorker.

4. From My POV

The thesis that minigrids are the silver bullet for Africa’s population without energy access remains credible. I fully get this, as I’ve developed and delivered several minigrids that have catalysed the local economy of remote communities across Nigeria, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sierra Leone, Mozambique, etc., amongst others. However, investment-wise, the story is not as straightforward. All of the minigrids I have delivered across these markets were financed through a combination of grants, concessional loans, patient impact funds, and minor local debt. I have worked on projects supported by public funds from The World Bank — Performance-Based Grant programme in Nigeria, Innovate UK Energy Catalyst (supported by 3 cycles of this programme), and similar sources of funding. Without these sources of funding, hardly anyone would be involved in minigrids today. Why? Because the numbers are difficult! Almost every country in Sub-Saharan Africa has some form of programme that provides result-based grants to developers in the minigrid sector, to derisk the sector and encourage private players to invest in the space. The investment stack of minigrids in most African markets relies hugely on the “income” or “CapEx contribution” from grants to make it work. I know this because I’ve lived it. I have hardly ever developed pitch decks for minigrid portfolios that didn’t include funding from a grant in their “Sources and Uses of Funds” slide. And I have developed quite a few decks for portfolios in this sector! To drive the point further, despite grant funding, a lot of projects hovered around the 9–12% IRR mark, in USD. This is obviously artificial as the return on Capital expenditure already ignores the capital contributed by the grant. Thus, rather than a 10% IRR on, let’s say, a full $1mn investment, it’s a 10% IRR on $600k investment since the remaining $400k will be provided through grants. Thus, if the full $1mn was invested, the effective IRR will be closer to 5–6%.

Let’s move away from the investment stack of minigrids and come to the development cycle and policy fragmentation. Although they don’t take the kind of long development time as grid-scale renewables, they still take considerable time. In my experience, my development time for minigrids, averaged across different markets, was about 1.2 years. From inception to commissioning. This included activities such as locating and accessing the community, community engagement, stakeholder management, demand estimation, design & engineering, permitting & licensing, liaison with authorities, international & local procurement, distribution network, setting up payment systems, raising (the remaining) investment, etc. Not to forget that these projects are also plagued by low demand, compared to peri-urban & urban centres, and thus, you have to stimulate demand as part of your project development by educating the community and financing some productive equipment for them, which hopefully, they would use more efficiently for their economic activities, and thus, use more power to make the minigrid investment case more worthy.

It’s important to say that I have enjoyed every bit of working on minigrids because, indeed, it is transformational for the final users. And it changes their lives in a way I can’t fully describe. I remember the king of one of the communities I delivered a minigrid at, in Ondo state, Nigeria, calling me on the phone to say, “Oga Dami, I thank you. The thing wey you talk say you go do, you do am. And my people happy well well” (Mr Dami, thank you. You did what you said you would, and my people are very happy) — he said in Pidgin after seeing how energy access from the minigrid was transforming his community. That’s one of the most notable things I’ve been told directly from a project beneficiary since I became active in the energy industry in 2016. I could see the huge smile on his face even though we had this conversation on the phone.

5. Verdict

Minigrids are transformative socially but misaligned with VC needs. They are best financed through blended finance vehicles, DFIs, and patient impact funds. For VC, the real opportunity lies in the software, fintech, or consumer-side platforms layered on top of minigrids, not the hardware infrastructure itself.

C. Commercial & Industrial (C&I) Solar Projects

C&I solar, rooftop or ground-mounted arrays (100 kW–5 MW) built for mines, factories, malls, hospitals, universities, or corporate campuses, is one of Africa’s fastest-growing clean energy subsegments. But despite its momentum, it remains more infrastructure-like than venture-like.

1. Market Landscape

Rapidly growing due to high grid tariffs, diesel costs, and unreliable supply.

Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, and South Africa lead adoption, with projects ranging from 200 kW rooftop malls to 5 MW mine-site systems.

Market estimated at US$9–11bn annually across Sub-Saharan Africa (IFC “Solarise Africa” analysis).

2. Typical Financials

Capex: $600k–$1mn per MW (lower than utility-scale, but still infra-like).

Revenue model: Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) or leasing agreements, typically 10–15 years.

IRR: 10–15% (sometimes higher than utility scale, but still project-finance style).

3. Case Studies

Solarise Africa (Pan-African C&I financier):

Raised $35mn+ debt/equity (from EDFI ElectriFI, Lion’s Head, etc.).

Portfolio includes malls, schools, and manufacturers in Kenya, Rwanda, South Africa.

Offers lease-to-own or long-term PPAs — essentially infra-financing packaged at SME scale.

CrossBoundary Energy (C&I arm):

Signed portfolio PPAs with Unilever, Diageo, Heineken breweries, mining companies.

Raised over $200mn to roll out distributed C&I solar across multiple African markets.

4. From My POV

The C&I segment is similar to the grid-scale segment in that they typically require a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA); however, this time, this is usually with a private client. This is another segment of the market where I have found a lot of success over the years. From Safari lodges in Kenya, Waridi resorts and Flower farms in Tanzania, manufacturing mills and gas stations in Nigeria, to banking institutions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, I’ve had a great deal of success in this market segment, both as a field operator and as a project developer. Most of these projects were owned by a London-based private investment fund that favoured predictable, long-term cash flow, locked in long PPAs. The fund I developed these projects for addressed currency risks by ensuring PPAs were negotiated to be paid in USD. We had much success with this arrangement in places like Kenya, DRC & Tanzania, but less so in Nigeria, where the glaring mismatch between the official and market rates of the Naira meant it was very difficult to find agreements since neither buyer nor seller was willing to take on this risk. Thankfully, Nigeria’s currency mismatch has found a stable horizon since the beginning of 2024, when both rates were paralleled, ensuring foreign investments could now expect less currency volatility.

My C&I field phase - powering gas stations with solar energy. I wasn’t always behind a computer, I started out on the field!

Like most renewable energy projects, each new project required significant capital expenditure, in my experience, mostly ranging from $250k-$750k, and growth is usually modelled as linear, not exponential. Most projects I worked on had internal rates of return in the early to mid-teens and retained ambitions to either be held long-term for the length of the PPAs, or to be sold to a bigger infra fund or yieldco.

5. Verdict

C&I solar is vital for industrial competitiveness and decarbonisation. It is an infra/debt/private equity play, not a venture play. VC might back platform layers (digital origination, customer management, or credit underwriting SaaS), but not the assets themselves.

D. Typical Home Installations (Residential Rooftop Solar)

Residential rooftop solar is often conflated with PAYGo solar, but it’s a distinct segment: larger, urban/suburban homes installing 1–20 kW systems (often with batteries) through direct EPCs.

1. Market Landscape

Found in middle-class and upper-income households in Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya, Ghana.

Drivers: frequent blackouts, rising grid tariffs, and desire for energy independence.

Systems are typically cash-purchased or bought with bank loans, rather than pay-as-you-go.

2. Typical Financials

Capex: $2,000–$20,000 per household (depending on size and batteries).

Revenue model: Direct sale; occasionally financed by consumer banks or vendor financing.

Margins: EPCs earn 10–20% gross margin per installation, but it is lumpy and project-by-project.

IRR: Relevant only at the household level (savings vs. diesel); for investors, there is no recurring revenue.

3. Case Studies

Lumos Nigeria (ex-MTN partnership): Initially blended PAYGo and rooftop, but found scaling urban rooftop challenging due to high customer acquisition cost. Pivoted toward simpler solar home systems.

South African rooftop boom: Post-Eskom load-shedding, rooftop PV capacity surpassed 4.4 GW by 2023 (NERSA stats) — but installed mostly via cash EPCs, financed by mortgages or personal loans.

Small EPCs: Thousands of local installers exist in Lagos, Johannesburg, Nairobi, and Accra. Highly fragmented, low barriers to entry, no clear VC-type scale advantage.

4. From my POV

As you would imagine, my clean energy career started with smaller residential home systems ranging from 2–15 kWp systems. These projects were vital in my introduction to clean energy transition, but they are simply not VC-type investments. This market segment is difficult to scale, and the market is limited to the middle-class population that can afford to make significant cash investments in the systems. Take Nigeria, where I grew up, for example, the population is over 200 million. If we assumed that the average household comprised 7 family members, then there are over 25 million households in the country, spread across its entire geography. This looks like a big market until you realise that the World Bank estimates about 47–56% of Nigerians live below the poverty line, essentially wiping off half of your market.

Another section of my field phase, installing solar for residential customers.

Furthermore, residential home systems literally require you to go to each residential home for installation, without a way to directly use the resources of one project for others. It’s a one-after-the-other market segment, requiring large teams to achieve any sort of scale. It also has no recurring revenues; I call it an install-and-forget model, except for minor O&M and repairs. Growth is fully tied to consumer affordability.

5. Verdict

Residential rooftop solar is an important part of Africa’s distributed energy transition, but it is not venture-backable. Attractive instead for mortgage lenders, green banks, and local EPCs. VC opportunities may exist in digital marketplaces (e.g., Solar Marketplace SaaS, embedded fintech for consumer loans), but not in the EPC business itself.

Summary of Not VC-able Segments

So far, under “Not VC-able”, I have touched on:

Utility-scale / grid-tied renewables

Minigrids

C&I solar projects

Residential rooftop installations

Each is critical for Africa’s energy transition, but their financial structures, risk/return profiles, and exit pathways push them firmly into infra/debt/PE territory, not VC.

VCs looking at Africa must resist the temptation to treat these as “startups” and instead focus on tech-enabled layers that can plug into these systems but scale like venture companies. Each is critical for Africa’s energy transition — but their financial structures, risk/return profiles, and exit pathways push them firmly into infra/debt/PE territory, not VC.

It’s essential to reiterate that these market segments are still viable, in fact, very viable. They are just not ideal for a typical VC.

III. The Real VC Opportunities

While much of Africa’s renewable energy landscape lies in infrastructure domains unsuited to VC, there exist compelling, high-growth corners where venture capital can, and should, play a transformative role. Below, I enrich your reading with deeper subsector analysis, grounded in real-world data, excerpts from my personal experience, and investor outcomes.

A. PAYGO Solar & Consumer Energy Access

These models are archetypal VC plays: scalable, asset-light, and data-driven.

M-KOPA

Stands as a flagship model:

Founded: 2011 (commercial launch 2012).

Model: $30 down payment + daily mobile repayments; >90% repayment rates; IoT-enabled upgrades and data analytics.

Customers & Credit: Over 6 million customers reached, with $1.5bn in credit extended as of mid-2025, Fintech Futures.

Smartphone Strategy:

Launched a smartphone assembly facility in Nairobi (“Africa’s highest-output assembly plant”) that generated over 400 jobs and produced 1 million devices in its first year, Tech in Africa.

Extended reach with bundled services like health insurance and embedded microloans, with 62% of customers using phones to earn income, and refurbished devices offered to boost affordability and sustainability, Fintech Futures.

Impact:

750k households (2019)

30% YoY growth, EBITDA positive

Social multiplier: children study more, kerosene eliminated, CO₂ displacement.

Recognitions: FT Africa’s fastest-growing, TIME100 influential, MIT 50 smartest.

Financial Performance:

Reportedly on track for $400mn in annual revenue by 2024, serving around 5 million underbanked users. Profitable operations in Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria, and Ghana.

IFC-backed sustainability-linked facility (~$200mn total) supports this scale, including local-currency funding for Kenya and Uganda expansions.

Together, these metrics signal velocity, scale, and a solid IRR pathway — exactly what VCs look for.

PEG Africa

A leading PAYG provider in West Africa, distributing ~25,000 solar home systems, enabling $1,000 in long-term savings per family, and providing hospital insurance to over 11,000 families.

Raised $7.5mn and won early awards like Ashden.

As an early mover in a region with traditionally low mobile-money adoption, PEG offers a unique regional case study for scaling PAYG models beyond East Africa.

These models blend tech, finance, and asset distribution — offering scalability, margins, and exits.

From my POV

This is one of the most VC-able segments of the market in Africa. My most recent trip to Nigeria made me understand why Sun King successfully raised $260mn in series D funding back in 2022 to scale their off-grid solar products business. It seemed like the country was living off Sun King appliances, as the average person seemed to have at least one Sun King product. And it didn’t matter what part of the country they were, I was in Lagos, Ogun, Oyo, Abuja, and Kwara over the course of this trip, and the story was the same across all these states. Sun King products were everywhere. It’s a simple PAYG model, with customers paying a small deposit and then making smaller, manageable payments over time. Remember the 47–56% population of Nigeria that lives below the poverty line that I mentioned in the residential home system section above; this is where they exist. This is where they are captured. Interestingly, Sun King is backed by General Atlantic’s climate investing equity fund, BeyondNetZero, whose co-founder and CEO, Lance Uggla, I had the opportunity to meet with in Barcelona earlier this year and discuss the climate tech market in Africa. It’s probably an understatement to say that Lance gave me and other colleagues a masterclass in the roughly 90 minutes we spoke. Interestingly, Sun King handles all its marketing and distribution across the country; it’s a complex yet successful model.

VC‑Verdict: VC-able.

B. Smartgrid SaaS & Energy Data Platforms

Software-driven models that boost utility margins and grid efficiency are gaining traction, though naming startups is less easy. Still:

Africa’s electricity grids lose upwards of 20% in transmission and distribution (T&D), creating fertile ground for SaaS tools (real-time metering, analytics, predictive maintenance).

These tools promise high margin monetization across geographies and utilities — making them quintessential VC-ready plays.

While still nascent in adoption, these platforms offer asymmetric upside with low incremental costs per customer — a hallmark of classic SaaS.

Notable companies in this sector include;

SparkMeter — grid management + smart metering SaaS for utilities and minigrids.

Odyssey Energy Solutions — SaaS platform matching capital with minigrid developers; also, energy asset performance reporting.

SteamaCo — cloud-based smart metering and utility management platform for minigrids and utilities.

From my POV

In the earlier part of my career, I also had the opportunity to work in a meter manufacturing and analytics company in Nigeria, within the Research and Development department. Here, I was involved in embedded systems, 8051 programming, IoT, communication protocols, metering, energy audits, etc. This is a market segment where software complements hardware nicely, with the potential to scale significantly as the same codes, solutions, technological architecture, etc., can be deployed across several geographies and utilities. Usually, I say, with software, almost anything is possible. And this is why this segment fits perfectly for VCs.

Back in 2016/2017, way before my “hair” journey.

VC‑Verdict: Highly VC-able.

C. EV Charging & E-Mobility Platforms

Africa’s fast-growing urban mobility markets have sparked innovative EV plays that marry hardware with recurring revenue.

Spiro

As of early 2025:

18,000 electric motorcycles in circulation,

11mn battery swaps, and

428mn CO₂‑free kilometers driven.

Recent financing: $63mn in debt capital from Société Générale and GuarantCo, earmarked to add 15,700 bikes, 31,400 batteries, and 1,000+ swap stations by 2025. Assembly plants in Kenya and Nigeria are set to scale production EV24.

Impact:

Deployed more than 60,000 LFP batteries across 8 countries.

Enabled 35,000 motorcycles with over 20 million battery swaps.

Supported by four African assembly plants and recognized as Africa’s fastest-growing battery swapping network.

Spiro targets 2 million bikes by 2030 and may approach $200mn+ in revenue in 2025, if deployment trajectory holds.

These facts illustrate how EV platforms can rapidly scale hardware and services while offering recurring, subscription-style revenue — a highly venture-appealing model.

Other Examples (Selected)

BasiGo (Kenya): Introduced e-buses in 2021; within six months, covered 150,000 km and served 155,000 passengers.

Ampersand (Rwanda): Battery-swap e-motos that allow drivers to earn ~35% more per day while saving emissions.

Zero Carbon Charge (South Africa): Raised R100mn (~$5.6mn) from DBSA to deploy solar-powered, off-grid EV charging stations along key routes, Tech in Africa.

These models combine hardware with tech-finance or SaaS elements. They’re growing fast and drawing climate and mobility funds.

From my POV

Again, hardware meets software platform, battery swapping, and recurring revenue. It hardly gets better than this. Marrying mobility with clean energy charging stations, battery swapping, and a subscription model ensures that this market segment penetrates the African market in a significant manner. It’s easy to see why this model is successful; it’s the PAYG model refined to suit this market segment. Your products here are the electric vehicles. Due to the significant CapEx of charging stations, you provide them for the clients through a battery swap model, and you earn recurring revenue, making it much more affordable for the consumers to manage payments and costs, without necessarily paying for services they don’t use. This ensures you capture a large fragment of the market, a significant portion of which is unlikely to be able to afford products like these as a one-time purchase.

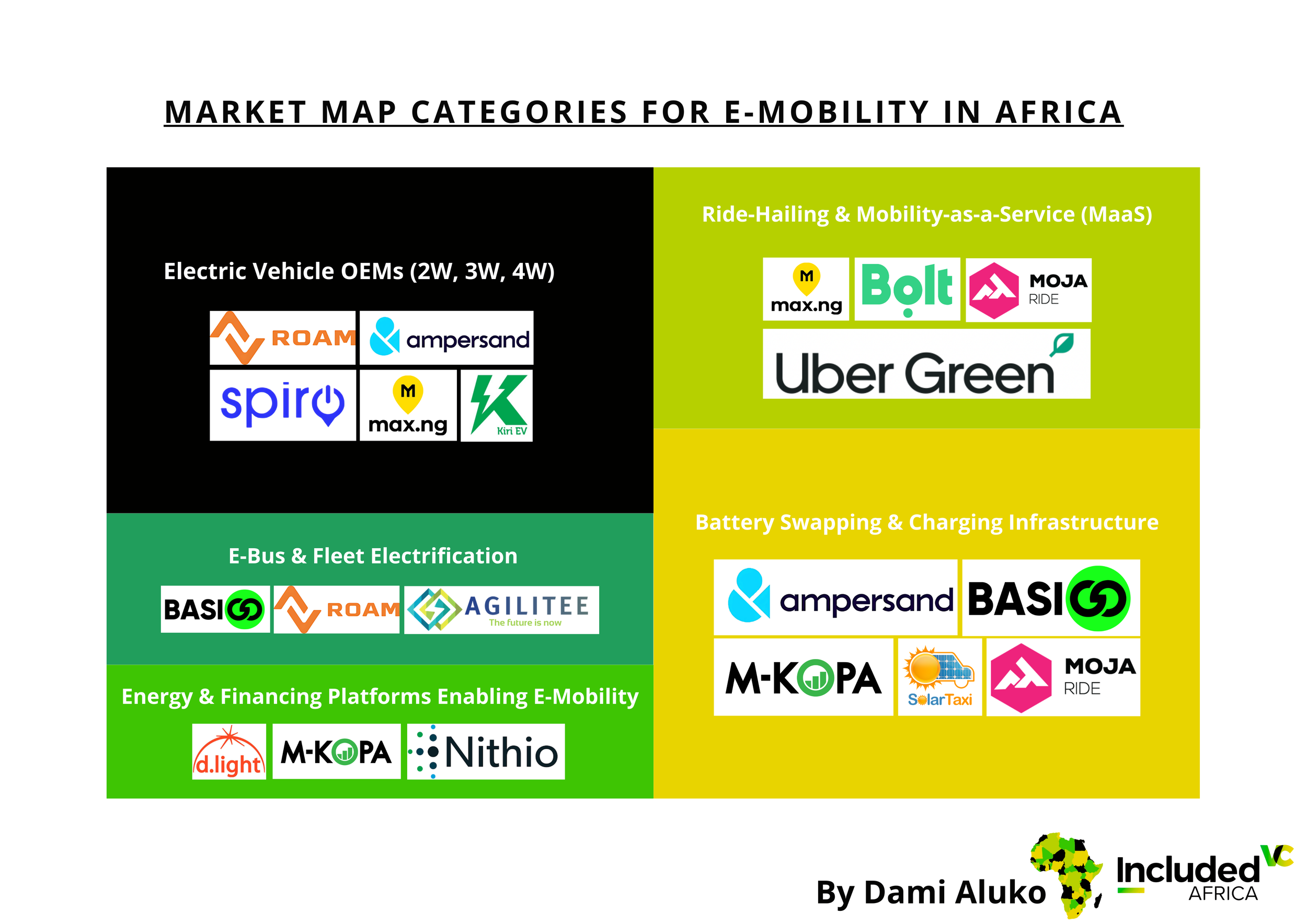

Visual landscape of e-mobility in Africa, showing select companies driving the market

VC‑Verdict: VC-able.

D. Carbon Markets & MRV Tech

As global buyers seek high-quality carbon credits, African startups offering digital MRV platforms are rising. Though nascent, these offer:

High-margin, software-heavy solutions.

Global export potential.

Strong appeal to climate-tech and institutional investors.

Notable early-stage companies in this space include the following;

Nithio Carbon - part of Nithio’s energy finance platform, building MRV for cookstoves/solar projects.

Cynk - building a carbon credit marketplace for African projects.

Solstroem - MRV + carbon credit generation from distributed renewable energy usage.

From my POV

This market segment is in its early stages, but has huge potential to blow up. The carbon credits market is more developed outside of Africa, and companies that can collect, collate, measure, and verify projects through digital platforms will make it big in this segment. Remember the project I mentioned in Ondo state, Nigeria, that project was completed in late 2022, and I managed to broker a sale of its environmental rights attribute to a top global tech firm in California for tens of thousands of dollars. This market will become very busy in the coming years. It’s a bet for the near future.

VC‑Verdict: VC-able.

E. Energy-Linked Fintech (Payments, FX, SME)

Energy infrastructure becomes a gateway to broader fintech services. Examples include:

Cross-selling loans, FX hedging, insurance, and SME credit to PAYG customers.

Data-driven underwriting and predictive analytics.

Tightly integrated stacks combining energy delivery with embedded finance — a highly VC-worthy convergence.

From my POV

One of the unfortunate things about a lack of data is that it excludes people from opportunities through no fault of theirs. My experience whilst providing energy access to people in remote and underserved regions is that these people usually have an economic system they religiously keep. Think of credit systems in the more urban and developed worlds. People in these remote regions have something similar, probably not just as technologically sophisticated as a credit card or credit referencing system. I’ve met people who save the same amount of money every week without fail, or those who turn over at high margins on their sales every day, in the local market. As a matter of fact, during the community engagement of one of the projects I worked on, I met at least 12 residents of a remote community who were conveniently Naira millionaires. For context, this would be equivalent to net worth> $200k. Want to know what their major economic activity is? Cocoa farming. The truth is, I’ve had the opportunity to work across various segments of the market, and every experience has built my knowledge base up to this point. I know something about almost all segments of the renewable energy market in Africa.

Engaging with some of the“rich” unbanked remote cocoa farmers during a minigrid development. The picture on the right is of me in the hotel room after a wet and rough day accessing a remote community. It’s not unusual that I get my hands dirty! Although I tend to spend most of my time these days behind my laptop, utilizing my prior field experience to provide support and advice.

What this market segment does is that, by layering fintech services on energy access, it banks the unbanked. I remember my first trip to Kenya years ago and how impressed I was with M-PESA. Literally everywhere I went, it was “Do you have M-PESA?” or “You can pay with M-PESA”. I probably heard this more often than I heard Mambo and Asante. I’m probably going off topic, but Kenya is beautiful, and I couldn’t recommend it more. Back to this market segment, consider layering M-PESA on all bill-paying consumers of the over 3000 minigrids on the continent. What do you get? A totally new market. A market one probably did not realise exists.

VC‑Verdict: VC-able.

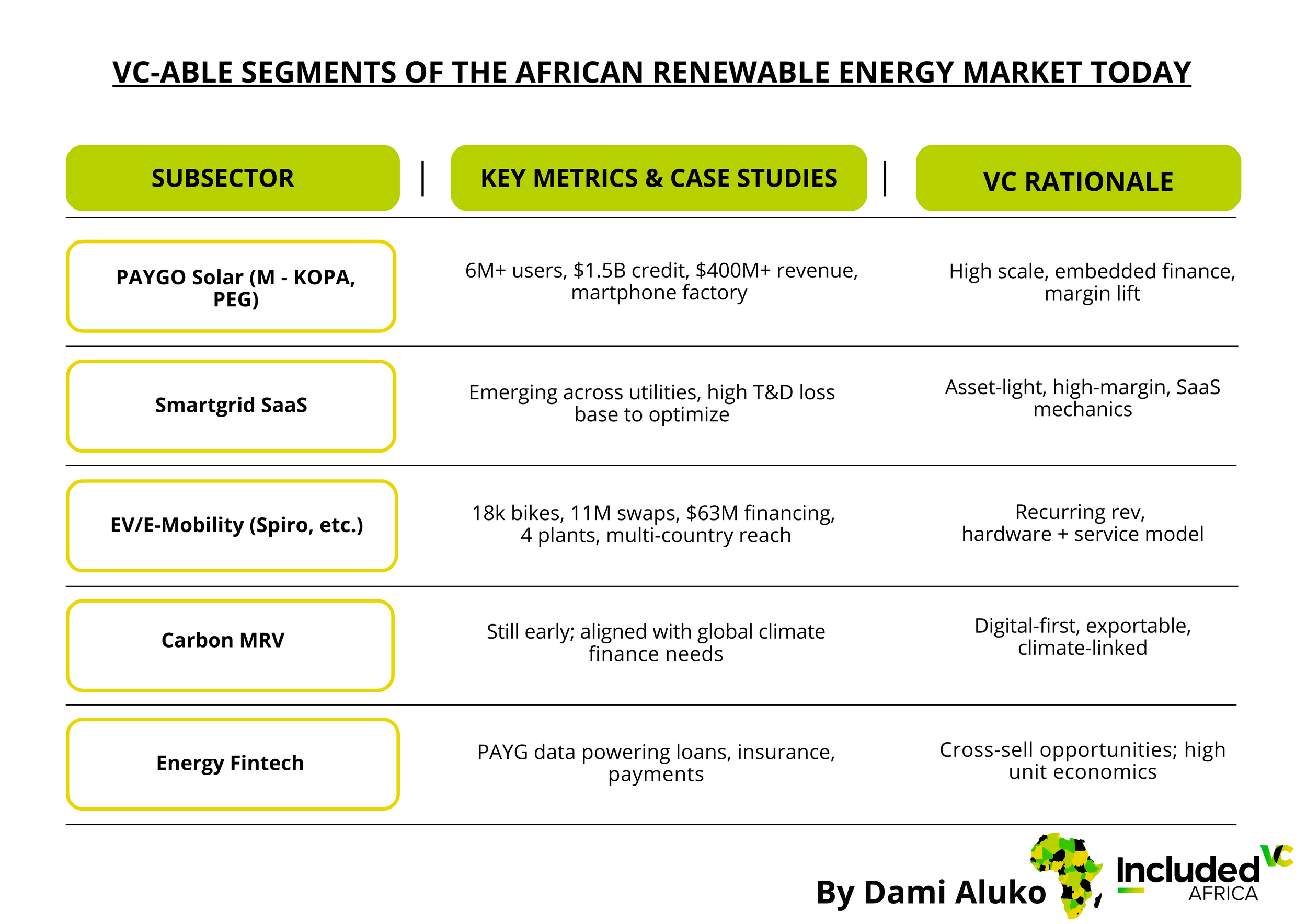

To wrap up the VC-able segments above, here is a simple table that provides a quick summary of my thoughts, as expanded upon above.

Why These Models Work for VC

Asset-lite or hybrid: They mitigate heavy capex burdens by digitalizing the value chain.

Scalable across borders: PAYGO, SaaS, Fintech, and EV models replicate quickly across markets.

High-margin potential: Emerging revenues from recurring services — loans, swaps, data — unlock robust unit economics.

Clear exit pathways: Acquisitions by tech or strategic players, or crossover to growth-stage funding.

High impact: They align financial return with energy access, emissions reduction, and systems efficiency.

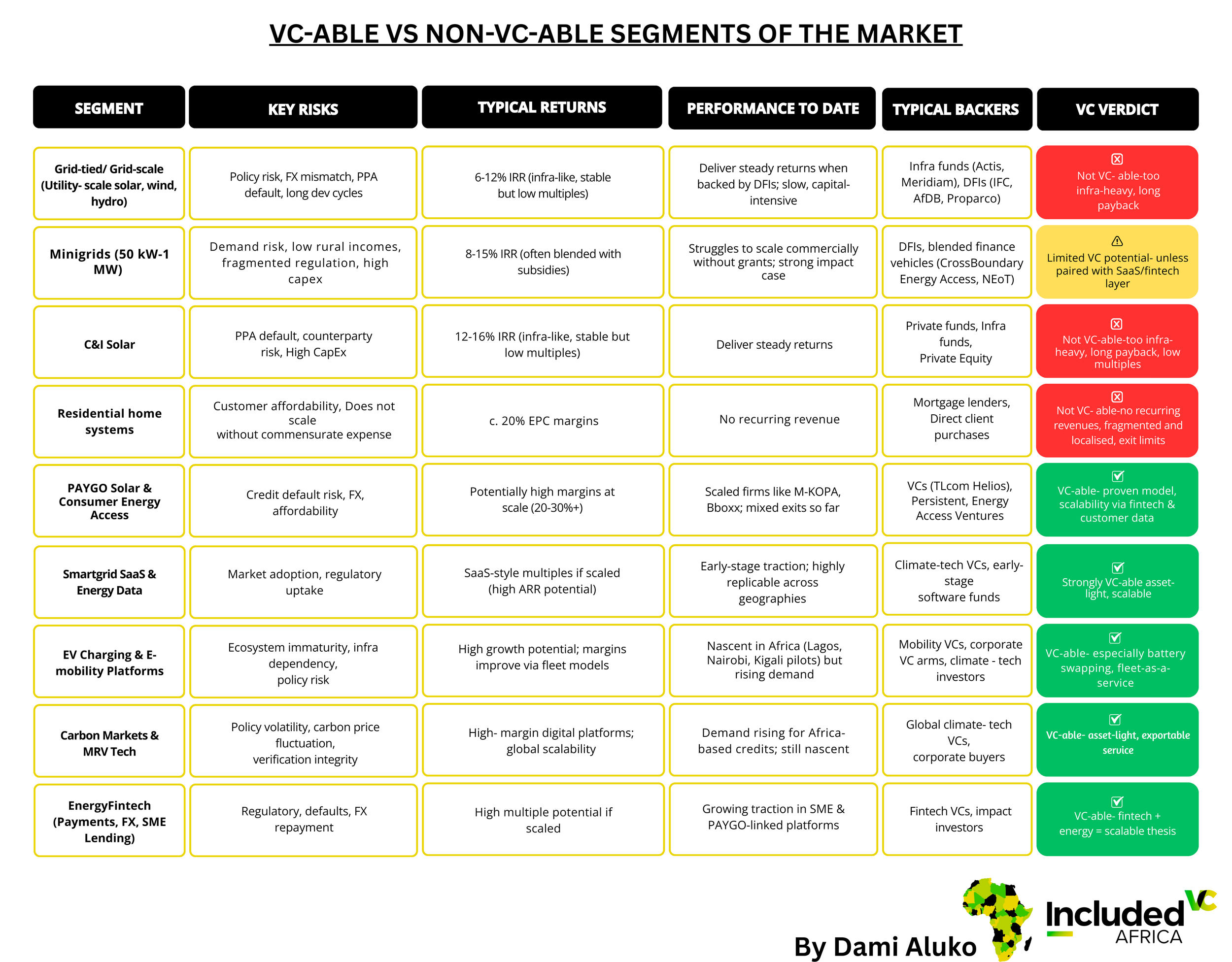

Having discussed both the VC-able and non-VC-able segments of the market, let’s look at them together, side-by-side.

Across Africa, grid-scale solar, minigrids, C&I solar, residential home systems, and transmission infrastructure fall squarely into the infra bucket, well served by DFIs, blended funds, and direct customer purchases, but offering little for VCs. This mismatch explains why grid investments attract DFIs, while VC remains skeptical. To win VC capital, renewable energy models need to shift structurally: less hardware, more digital, more consumer-facing, more scalable. Emerging tech layers: PAYGO platforms, SaaS, carbon tech, etc., are positioned more squarely within the VC playbook.

VC money will not transform Africa’s utility-scale power generation, C&I space, or residential home systems. But it can transform how power is financed, accessed, distributed, and paid for. That’s the heart of what’s “VC-able.”

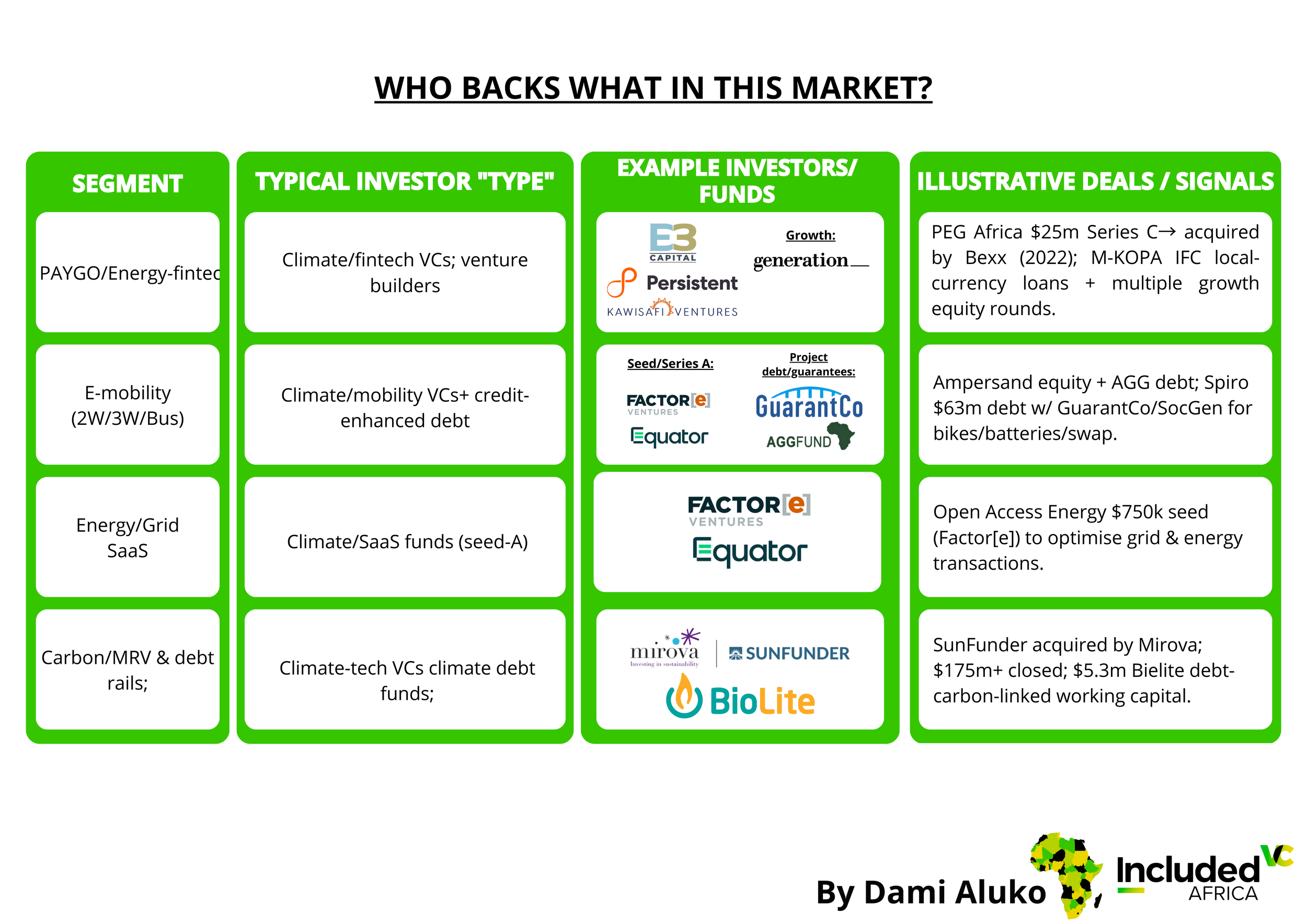

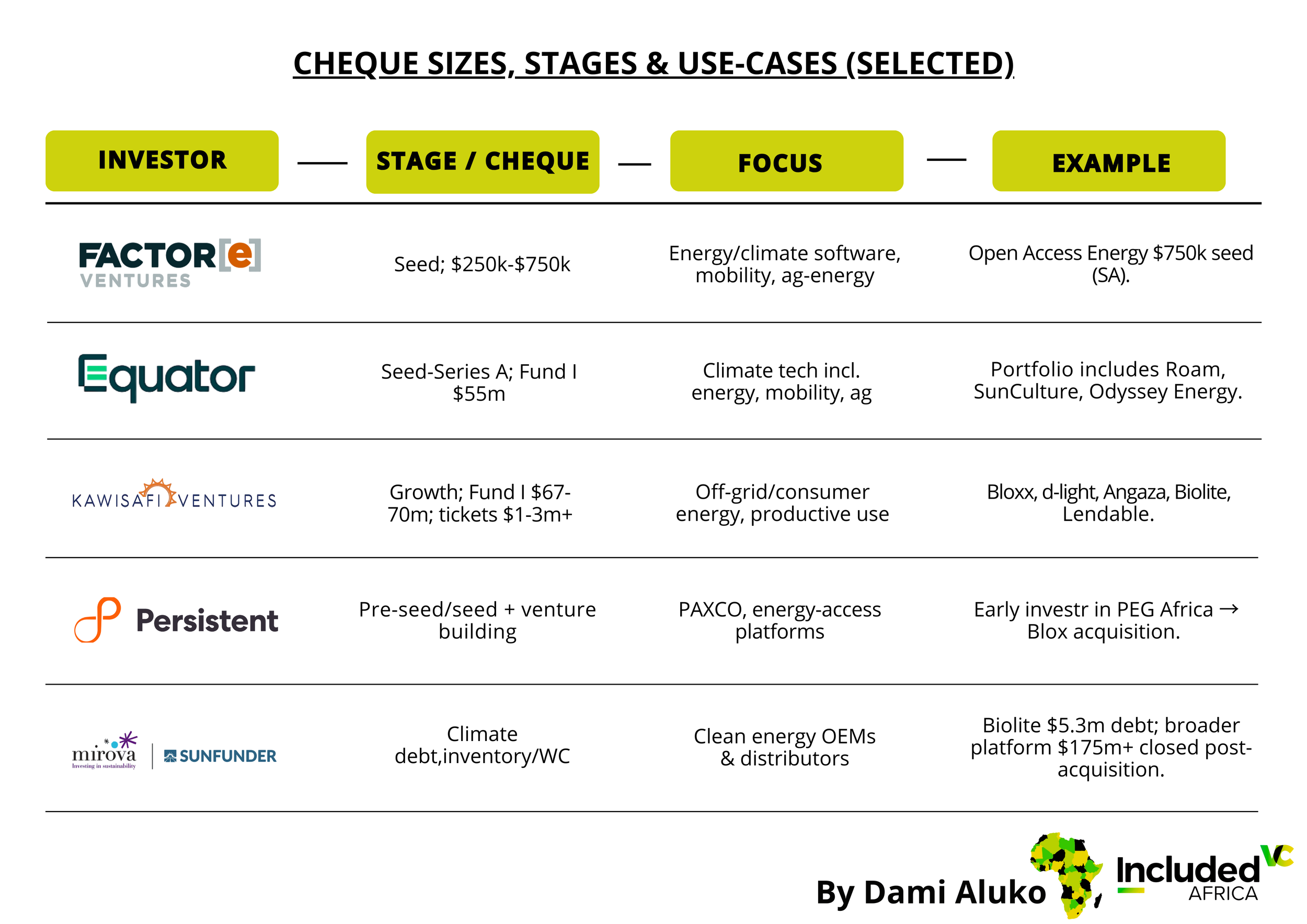

IV. VC Investor Profiles Across Segments

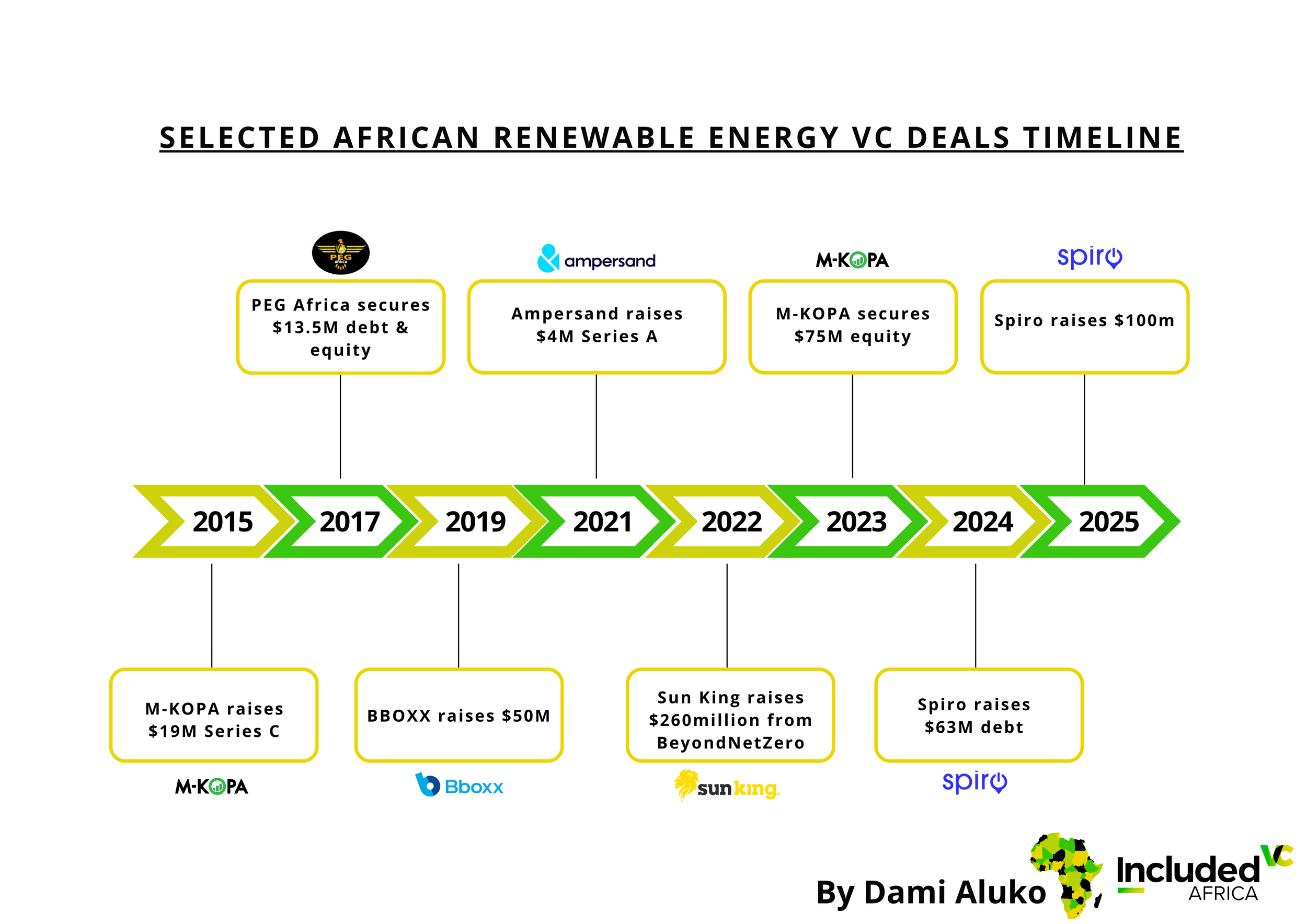

Now that we’ve discussed the VC-able segments of the market, let’s look at some of the activities in the sector that corroborate our earlier discussion. Below is a mapping of some of the notable active participants, what they fund, the proof points (deals, exits), and the signals these send for your “VC‑able” thesis.

A. PAYGo / Consumer Energy & Energy‑Fintech (core VC‑able)

1. Persistent (venture builder + early VC)

Thesis: Venture building and early checks into energy‑access businesses; helped seed and scale PEG Africa (PAYGo SHS), among others.

Signal deal: Persistent was the first investor in PEG Africa; PEG later raised a $25mn Series C (2019) and was acquired by Bboxx (2022) in a clean, strategic consolidation outcome in PAYGo.

Recent fund‑raise context: FSDAi supported Persistent to raise a $50–70mn climate‑fintech/energy‑access vehicle, a good signal of LP appetite, FSD Africa.

2. E3 Capital (ex‑Energy Access Ventures) / E3 Low Carbon Economy Fund

Thesis: From access to energy to broader climate-smart, “digitised/decentralised/decarbonised” solutions; figures point to $150mn raised, 26+ portfolio, 22 countries.

Lineage: EAV Fund I backed off-grid/energy‑access SMEs; now E3 Low Carbon Economy Fund (with Cygnum Capital) broadens into climate tech.

3. KawiSafi Ventures (Acumen‑anchored growth VC)

Thesis: Growth capital for off‑grid / consumer energy in East Africa; Fund I ≈$67–70mn; portfolio includes Bboxx, d.light, Angaza, BioLite, Lendable, etc.

Recent activity: AfDB committed $10mn to KawiSafi II; portfolio reports 213mn lives impacted and 45mn tCO₂ averted (as of Q3‑2024).

Why it matters: KawiSafi is a later, scaling‑stage complement to early investors like Persistent/E3.

4. M‑KOPA’s capital stack (as a bellwether)

Debt + local‑currency: IFC extended a $50mn equivalent multicurrency loan to the Kenya entity and UGX‑denominated facility to Uganda, a textbook FX mitigation aligned with PAYGo revenues.

Growth equity: Led by Generation Investment Management (2015, 2021), among others, a useful precedent for later‑stage climate‑fintech crossovers.

Takeaway for founders/VCs: This layer is VC‑able when you see embedded finance + local‑currency debt lines + data‑rich cohorts. Consolidation by strategic buyers (e.g., Bboxx PEG) provides credible M&A paths.

B. E‑Mobility / EV Platforms (VC‑able hardware‑plus‑network plays)

1. Ampersand (Rwanda; e‑motos + battery swapping)

Capital: From early checks (EIF’s $3.5mn 2019) to $19.5mn equity + $7.5mn debt (2024/2025 packages involving Africa Go Green/Cygnum, BII and others).

Model signal: Battery‑swapping reduces rider OpEx, boosts daily earnings, and enables recurring revenue, aligning well with venture growth

2. Spiro (multi‑country; battery‑swapping e‑motos)

Capital: $63mn debt from Société Générale & GuarantCo (partial guarantees), scaling 15,700 bikes, 31,400 batteries and 1,000+ swap stations. This is the credit-enhanced CapEx pattern VCs like to see alongside equity.

Operating scale (2025 reporting): Tens of thousands of bikes; millions of swaps; multiple assembly plants, a credible path to platform status.

Takeaway: E‑mobility wins when there’s (i) swap/charging density, (ii) credit‑enhanced fleet capex, and (iii) local assembly to compress unit cost. Spiro/Ampersand show how guarantee structures pull in banks.

C. Energy & Grid SaaS / Data Platforms (VC‑able, asset‑light)

Who is active:

Factor[e] Ventures (seed) and Equator (seed/Series A) back energy‑software and climate‑ops tooling; Factor[e] tickets $250k–$750k; Equator Fund I closed $55mn with IFC/Proparco/BII LPs.

Illustrative deal: Open Access Energy (South Africa) — Factor[e] invested $750k seed for grid‑/energy‑optimization software (2024/2025), now a common pattern as utilities and C&I customers digitize.

Why VCs care: 20%+ T&D losses in many systems = huge software TAM for loss reduction, AMI, billing, demand response, high‑margin, cross-border roll‑outs.

D. Carbon / MRV & Climate Finance Rails (VC‑able “exportable” software)

Debt platforms & blended vehicles supplying carbon-linked inventories and receivables are maturing:

Mirova SunFunder (post‑acquisition of SunFunder by Mirova) has closed $175mn+ in facilities and continues to run clean‑energy debt for SHS/productive use providers. They also financed BioLite working capital ($5.3mn debt) as the company scales clean‑cooking with carbon‑revenue strategies.

Why VCs care: The MRV/data layer, digital measurement/verification, registries, and receivables financing can be software-first with global demand.

V. Conclusion & Playbook for VCs

Africa urgently needs energy, and VC has a critical role to play, but where and how matters deeply. VC capital should:

Avoid infra-heavy bets, where expected returns don’t match VC risk-reward.

Zero in on asset-light, digital-first, consumer-facing models:

PAYGO solar scaling in consumer markets.

Smartgrid SaaS turning inefficiency into data margins.

E-mobility where fleet economics are reshaping transport.

Carbon MRV platforms enabling global climate finance.

Energy fintech as the gateway to broader digital services.

VCs that deploy finances in these areas can unlock scalable impact and financial return, while shaping Africa’s clean energy future. Africa doesn’t need infrastructure masquerading as venture capital. It needs VCs who know precisely where the venture models lie, and who can back them with discipline, insight, and structure.

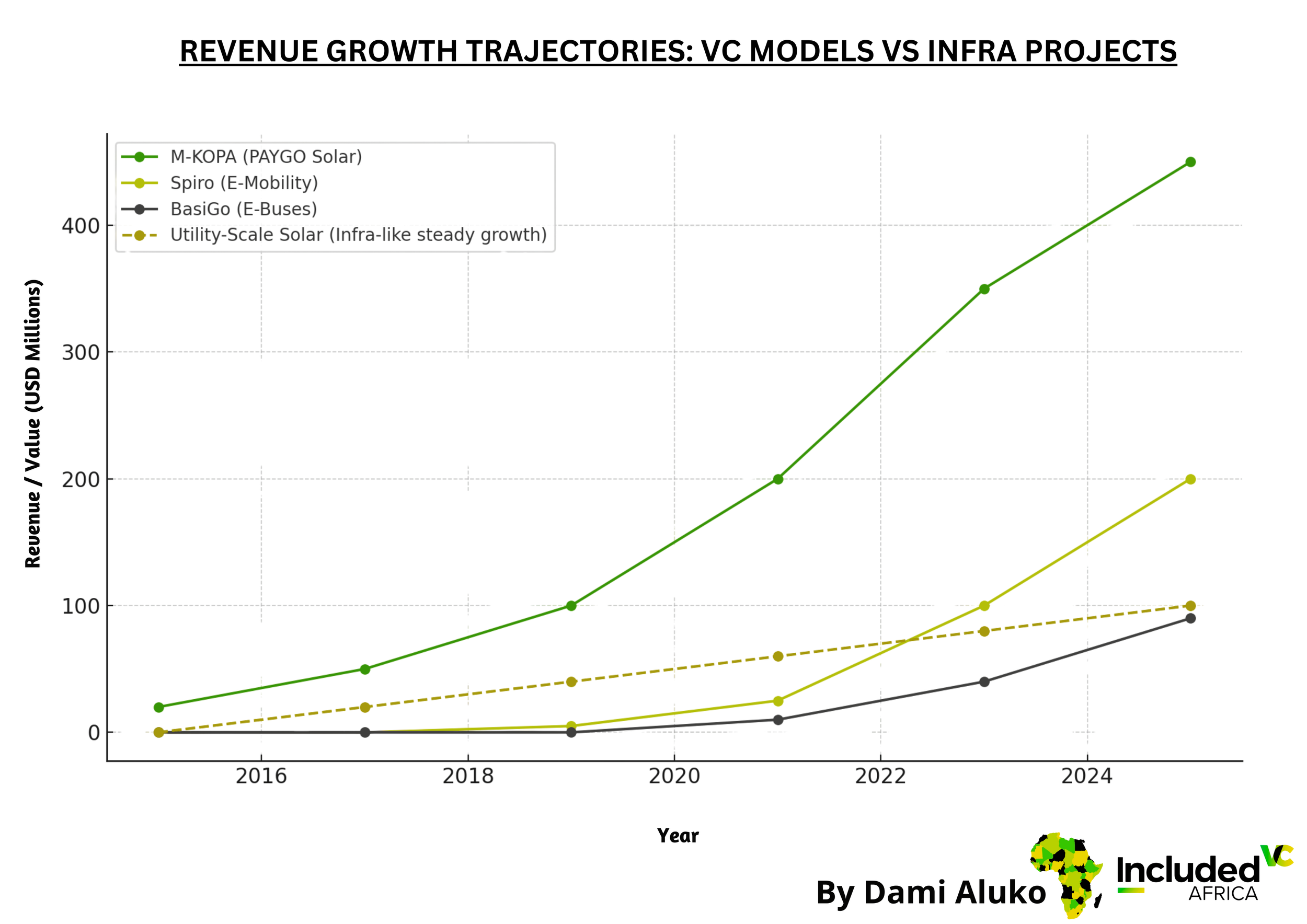

I leave you with a picture showing the revenue growth of VC-able segments compared to infrastructure, a final reminder of the opportunities that exist within the African renewable energy space. With this, I yield my pen (keyboard).

Dami Aluko works at the intersection of clean energy, data, investment & technology. Primarily based in the United Kingdom, I help organisations design smarter grids, scale distributed energy, and unlock climate-tech opportunities. My 10-year industry background spans C&I solar, demand-side response innovation, minigrid systems, technical–commercial modelling, smart grid strategy, energy data analytics and project finance for clean energy infrastructure.

If you’re keen to have a chat about anything I’ve written, feel free to reach me directly at: damilarealuko@gmail.com.

Let’s build a cleaner future for the planet, together!